David Lynch made mysteries. Who killed Laura Palmer? Who killed your wife? Whose ear is that? Who are you? What the fuck is going on? Crimes to solve, puzzles to piece together. I’ll spend the rest of my life messaging friends new revelations about his work: a number decoded, a connection uncovered.

The magus was a stylist, too, curator of a specific neon-sexy bloodgore region of throwback Americana. You can’t sum him up: He could do meta and he could carve wood, he was the cinema artiste making selfie web videos pre-YouTube.

There’s a special feeling in all his projects, though, deeper than mystical enigmas or fashionable snazz. A familiar, remarkable warmth. Some saw that tone as nostalgic, retro, overly affected in contrast to his nightmare visions of evil. It was once possible, I think, to read his gee-whiz sincerity as parodic: The Hardy Boys Meet Cthulhu. Was he more interested in the horror? Because he died today, the end of his directorial career will always be the disturbing, upsetting, fearfully ambiguous ending of 2017’s Twin Peaks revival. (Unless you count What Did Jack Do?, the short film where David Lynch is the detective interrogating the monkey who is also David Lynch.)

But the 18 hours of miniseries preceding that downbeat climax offer levity, generosity, community, humanity. In one sequence, a boy crosses a street. A truck blows through the stop sign — and through the boy. The child’s mother screams, runs to him, cradles his dying body. The only familiar actor in this scene is Lynch’s (very) old friend Harry Dean Stanton, who watches from the sidewalk. He sees a strange gold ambience rise from the little corpse into the sky. Then Stanton comforts the mom without saying aything. The camera cuts to onlookers and bystanders, all sad, some holding each other, others moved to tears.

There is something cozy in their horror. I’m talking about a Dead Kid scene here, but it’s a death scene full of life, overflowing with the palpable sense of a deep human connection forming in response to unthinkable loss.

Twin Peaks has a cosmology, the Black Lodge and the White Lodge, which you could vaguely describe as Hell and Heaven. One place grows demons, the other sends angels. But I’ve rewatched Twin Peaks enough to suspect the truth is much stranger. I think the Black and White Lodge are the same location — that they’re right here around us, in fact, separated only by perspective. The worst place in the world and the worst moment of your life always contain the capacity for grace. Heaven is Hell, which only sounds like a bummer if you don’t realize Hell is also Heaven. Even terror is full of wonder. At terrible times in my life, I have felt grateful to David Lynch for helping me to see the wonder.

He was a director, a writer, an actor, a composer, a sound designer, a coffee impresario, a meditation tycoon, a vlogger. You could reasonably declare he made the best movie and the best television show — though, typical paradox, his most acclaimed film was planned as a network drama and his most acclaimed TV show became one (or two?) movies. Lynch soared and plummeted twice before I ever learned about him. Eraserhead was an outsider midnight-movie trip, The Elephant Man a surreal Oscar-nominated hit, Dune a bloat-budgeted failure. Then Blue Velvet was an arthouse sensation that led to Twin Peaks’ popular phenomenon.

The show died a year after its premiere. A prequel film flopped. In his semi-memoir, Room to Dream, Lynch remembered the bad aftermath of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. “It was just one of those times in life when you can’t get arrested. Oh man, that was a horrible, horrible, stressful time, and I got really sick.”

Some years later, my older brother very older brother-ishly showed me Lost Highway — mindblowing stuff for a barely-teenager. Lynch truly rebounded with Mulholland Drive, the first one of his films I saw in theaters. Because his work was often indescribable in human language, you’ll be reading a lot of sincere, lofty, rather vague pronouncements about his output. The French do love him in their French way. But Mulholland Drive was also Hollywood and hip, a reality-warping twist movie when that was vogue, meta enough to stunt-cast Billy Ray Cyrus, erotically lesbian right as the coolest young starlets were making out in Wild Things and Cruel Intentions.

Understand, I’m not saying Lynch was chasing fads. Arguably he invented multiple trends, including the modern puzzle-box narrative; his TV influence spread from The Sopranos to Lost, from confessional artcoms to neon-retro soap operas. In hindsight, though, Mulholland Drive was the last time one of his creations came close to the mainstream. Inland Empire arrived years later, three hours long, shot on ugly video that looks curiously immaculate now that it’s a lost visual effect. That was his last movie, unless you count the 18-part revival of his TV show, which miraculously appeared in 2017.

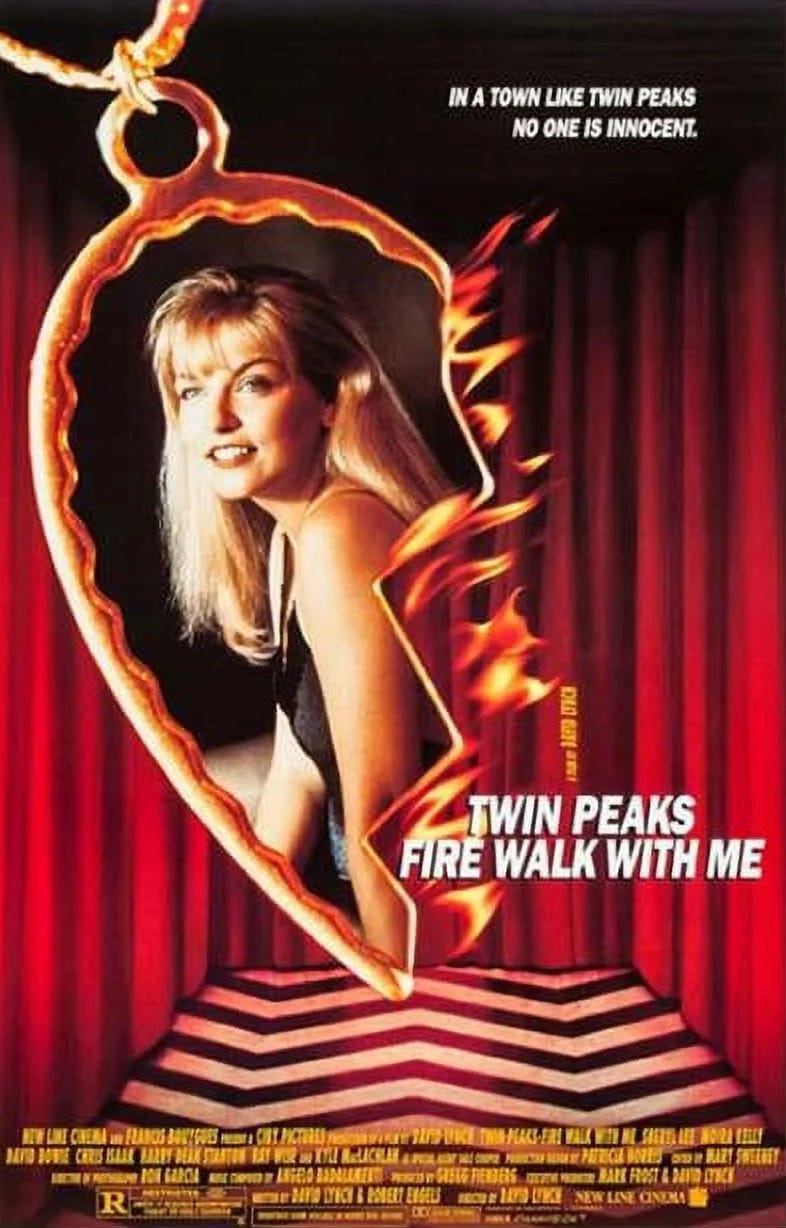

I would recommend watching any of his movies tonight — I may show the kids The Straight Story, it’s G-rated! — but my first thought when I read about his passing was, inevitably, Twin Peaks. In its original incarnation, the show was a small-town mystery. A teen girl, Laura Palmer, washes ashore dead. FBI Agent Dale Cooper investigates her murder. Everyone is a suspect — including people who aren’t people. The show wound up revealing Laura Palmer’s killer. Lynch was unsatisfied with the answer or any answer. Without co-creator Mark Frost, he made Fire Walk with Me, an expansion and a distillation of his Twin Peaks vision.

I have watched the movie more than any other David Lynch project. I think it’s my favorite of all his works, which means it’s one of my favorite things ever. But I can understand why people hated it, or still find it baffling. It throws a lot your way — David Bowie, Chris Isaak, a red-haired dancing woman, a trailer park, screaming kids in a school bus, Lynch himself onscreen as screechy half-deaf Gordon Cole. Kyle MacLachlan, the star of the series, barely appears. In cruel corporate modern film lingo, Fire Walk with Me is a spin-off that requires you to know a lot about a franchise while ignoring almost everything the average person enjoyed about the franchise. (I’m only half-joking when I say: Think Madame Web.)

The main focus, though, is Laura Palmer. The show began with her death. So focusing on her last week alive could feel pointless or unnecessary. But the inevitability of her murder is crucial. As played astoundingly by Sheryl Lee, Laura often comes off half-dead already: Strung out on drugs, assaulted in her home by her own father who is also a kind of demon, misunderstood by the men and boys who say they adore her, embedded in a couple downbeat crime plots. “Your Laura disappeared,” she tells one lover, “It’s just me now.” Nobody understands her. Maybe we don’t either, really; maybe Lynch didn’t, either; maybe that’s why he loved her so much. But the film demands you to honor her life, and any life like hers. Her killing is not the end. We find the dead girl in another place, existing in an indecipherable state of being — which nevertheless seems full of ecstasy, ascension, triumph.

Years later, impossibly, the character returned in the Twin Peaks revival. “I am Laura Palmer,” she says at one point. “I am dead, and yet, I live.” Same with David Lynch.