Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 'Warriors' makes an unforgivable mistake

When good intentions miss the whole point

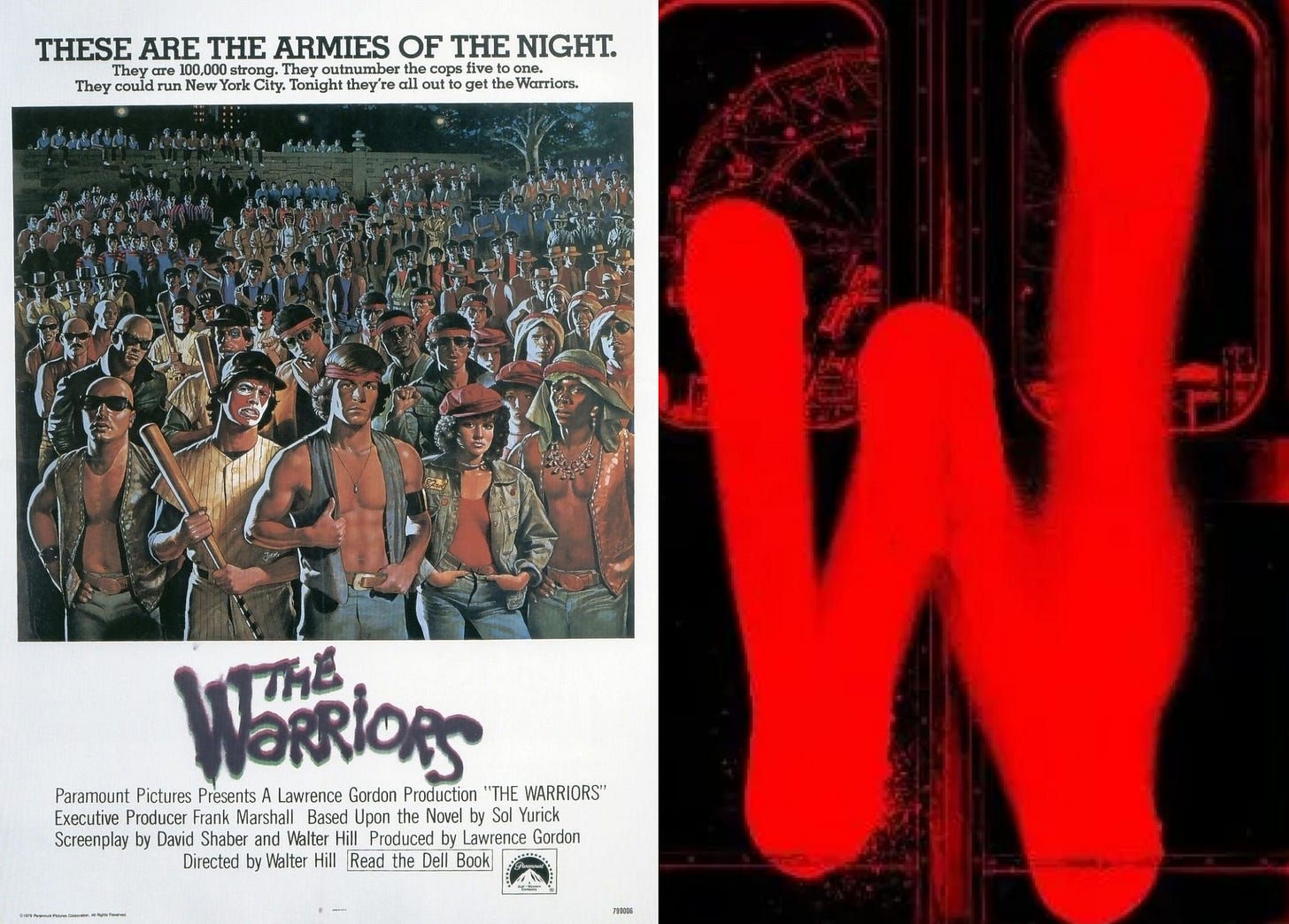

A gang from Coney Island gets stranded up in the Bronx. Everyone wants them dead. A simple, awesome premise: Cross the City, Fight the City. We could’ve had twenty versions of The Warriors by now, but there was never a proper sequel or remake for Walter Hill’s 1979 movie until this month. I love how the film is a barely-franchised wonder thing. I am also, however, semi-obsessed with it. In 2005, I bought the (terrible) Director’s Cut DVD and played the (wonderful) video game. So I was amped for Warriors, a new album by Lin-Manuel Miranda and Eisa Davis, which reimagines the saga in song.

Just your basic Miranda guy here: Cried at Hamilton, put Moana on the jogging mix, loved him on DuckTales, did not like his kinkajou cartoon, hated him in Mary Poppins Returns. It’s possible I’m an Encanto dad; when I played Warriors on the way to drop-off, my older son said, “Can we listen to the Luisa song?” He heard the Miranda telltales: synth percussion, rapidfire rhymes, dialogue half-sung half-rapped. The worst thing you can say about his catchy music is it’s dorky sometimes, but there’s already something Band Geek-ish in The Warriors. The movie’s baddies are costume-closet scum: Baseball clowns, skaters, semi-lesbian sirens. The tough-guy Warriors wear skinny vests baring adorable tummies. They fight on a subway platform, in a bathroom, on the beach. All in 90 minutes, the perfect running time! (Currently streaming on Paramount Plus.)

I was hopeful about the concept album. I knew almost nothing about it. I learned four things fast after hitting play:

1. It gender-swaps all the Warriors into women.

2. It’s a sincere attempt to capture the diverse music of New York.

3. It features Lauryn Hill as doomed gangster overlord Cyrus.

4. It sucks.

The first three facts need not equal the fourth. A lady-squad mission set to hip-hop, Latin dance, a bit of pop-punk and neo-soul: Cool in theory! The film’s diversity deserves points for surrealism — Lynne Thigpen’s DJ as the taunting Greek Chorus, a Manhattan ruled by Black martial artists from Gramercy— but the album is expansively multicultural, and more explicitly (less judgmentally) queer. Even a failed Warriors rap opera full of celebrities (Marc Anthony!) should be entertaining. It's funny how the lame gang sounds ska and the seducer gang sounds Boyz II Men.

But Miranda and Davis get this story wrong. Warriors seeks redemption in a tale of human cockroaches squirming across the carcass of metropolis. These Warriors need to be Good — not just women but Great Women, Excellent Humans, people to vote for. In the process, Miranda and Davis make an unforgivable mistake. They let Cleon live.

In the movie, the leader of the Warriors is the first face we see. Actor Dorsey Wright was crazy young, 22 if that, but he’s the dominant figure in a leopard-print bandana. The War Chief provides us with exposition: Every gang is heading north for a rare assembly. There, the magisterial Cyrus tries convincing the assembled crews to join together. When he’s shot dead, Cleon’s the lone Warrior who runs to his side. Accused of the murder, Cleon fights a dozen men, before falling under the sharp elbows of the vengeful Riffs.

Online summaries say Cleon dies. In fact, we just see his body disappear beneath the mob. His friends never find out what happens to him. The vanishing creates a whiplash. Cleon and Cyrus, the initial alpha personalities, exit simultaneously. The Warriors’ outrageousness is grounded by those genuine shocks, the feeling anything can happen to anyone. It's a genuinely experimental scrambling of main-character focus. The nominal bad guy doesn’t even meet our heroes until the end, because [deep breath] the true antagonist is New York City. (By contrast, Hill’s later Streets of Fire, a much more elaborate gang dystopia, tells an old-fashioned story about a Good Guy and some Bad Bikers.)

In the new Warriors, Cleon (played by Aneesa Folds) survives. Captured, she promises she’s a true believer. “We came to hear the truth and be moved, be in your movement,” she tells Cyrus’ lieutenant. Worth noting, Movie-Cyrus is not a utopian activist. He pitches criminal cooperation as the path to conquest: take the boroughs, tax the syndicates, tax the cops. He’s a violent demagogue in a violent world — a warrior. Lauryn Hill’s a legend, but nobody’s casting her for moral ambiguity. Album-Cyrus does not discuss taxation. She urges her flock to “stand together against dangers.” The resurrected Cleon becomes the keeper of Cyrus’ legacy, declaring:

We can still go and rebuild the world

Until we reach the peace Cyrus was seekin’

What do you do when they kill everything you believe in?

You lean in.

A street boss quoting Sheryl Sandberg: You’re getting a sense of Warriors’ perspective, some generalized boardroom feminism plus up-with-everybody goodwill. Whereas the movie’s landscape is ruined and awesome, full of young people trying to have illegal fun without getting murdered. No gang is all good. The hope with any gender swap is to make things more interesting, adding exciting complications to a familiar story. Warriors sands away the edges. Police are a more consistent threat, but in the movie, every system is a threat, whether it’s the law enforcement overworld or any black-market criminal power community. The Warriors can’t depend on the law or the lawless, can’t even entirely trust their own teammates. Ajax, the Warrior who onscreen is jerky or outright malevolent, gets softened considerably in the remake. Surely one woman in seven can still be an asshole?

The album ends with Cleon reuniting with her gang. Their closing number promises a new beginning: “This is the sound of something being born.” I prefer the film’s conclusion, a walk down the sand while “In the City” plays. “I know there must be something better,” Joe Walsh sings, “But there’s nowhere else in sight.” The new Warriors wants to show you Better. It’s on-message, anxious for approval, like someone turned graffiti from a vacant building into street art for an office wall. The movie, by comparison, doesn’t think Better exists. Cynical, maybe, but the nice thing about living in the ruins is nobody minds when you come out to play.